Dr. Saroj Ghose

Prelude

Dr S Hussain Zaheer, then Director General of CSIR, was in his office at Delhi in a very relaxed mood after a post-lunch brief nap. That was in the last week of March in 1965. A young Curator, just returned from the USA to take charge of the Birla Industrial & Technological Museum (BITM), met him on a courtesy call. 'Young man, what new ideas have you brought from the USA for your museum?' - Dr Zaheer asked in a casual note. Starting hesitantly but slowly picking up, the Curator unravelled his dream of a large fleet of Museobus taking science to the deep interior of the country. With closed eyes Dr Zaheer gave a patient hearing and uttered just two words - 'go ahead'. The interview was over.

Fresh in his mind, the young Curator remembered his exposure to the world's first mobile art museum, the Artmobil of Richmond, Virginia, taking paintings to the door of common man since 1953. He remembered the mobile ethnographic exhibition organised by the UNESCO for some of the West African countries in the late 1950s. In both cases static artefacts, paintings and ethnographic materials to be precise, were mounted on what was then called the Museobus or a museum on wheels. The term museum was associated with both these mobile ventures. These two examples inspired the young Curator to plan for the world’s first Mobile Science Museum or MSM carrying working didactic exhibits on science and technology. It is not known whether any other mobile science museum or regularly running travelling science exhibition predated the one developed in BITM in 1965, but definitely there was none like one that, over the years, would flourish to a fleet of 25 museobuses criss-crossing the length and breadth of a vast country.

Why was it necessary to float a dream project like MSM at all? By 1965, the planners of the country were already talking about the need for instilling scientific temper in the society to fight superstition and obscurantism. With a low literacy rate, particularly in rural hinterland, science museums were considered an effective platform for non-formal science education. Moreover with increasing democratisation of the society, museums thriving on public funds had more accountability to the people. Although the BITM was able to draw a sizeable crowd, including large school groups from the city and its suburbs, the people in the adjoining districts hardly visited the BITM. The concept of MSM emerged with a motto: if the people do not visit the museum, let the museum visit the people at their doorstep. If the people are not museum-minded, why not the museum be people-minded? The BITM therefore felt that going to the public was a dire necessity.

Three important decisions were taken even before starting the project. First, in keeping to the character of BITM, the MSM shall have working didactic exhibits explaining the basic principles of science, no matter how difficult it could be to keep the exhibits in working order on road. Second, MSM shall not be confined only to the suburb areas of Calcutta, coming back to its garage in BITM every evening, but shall penetrate the deep interior of the country with tours lasting for four to six weeks at a stretch and staying on road for nine months a year. Third, the project shall be time bound to be on road on the next National Children's Day on 14 November, 1965.

But it was not easy to see the dream come true. The idea of taking the museum out of the four walls was a major departure from the standard definition of museum. Apart from the requirement of additional funding, it required a radical change in mind-set of the people who would sanction the project. Soft tapping of the members of the Executive Council revealed hesitation, if not reluctance, to give a nod to this unusual project and the CSIR expressed inability to allocate extra-budgetary fund until the revised estimate is approved at the end of the year. The young Curator made a desperate dash to Delhi, and almost gate crashed into the chamber of the Director General of CSIR. Dr Hussain Zaheer, sitting on a sofa, listened with closed eyes and again said, just two words, 'go ahead'. Within next two weeks the approval came from Delhi

Two inaugurations

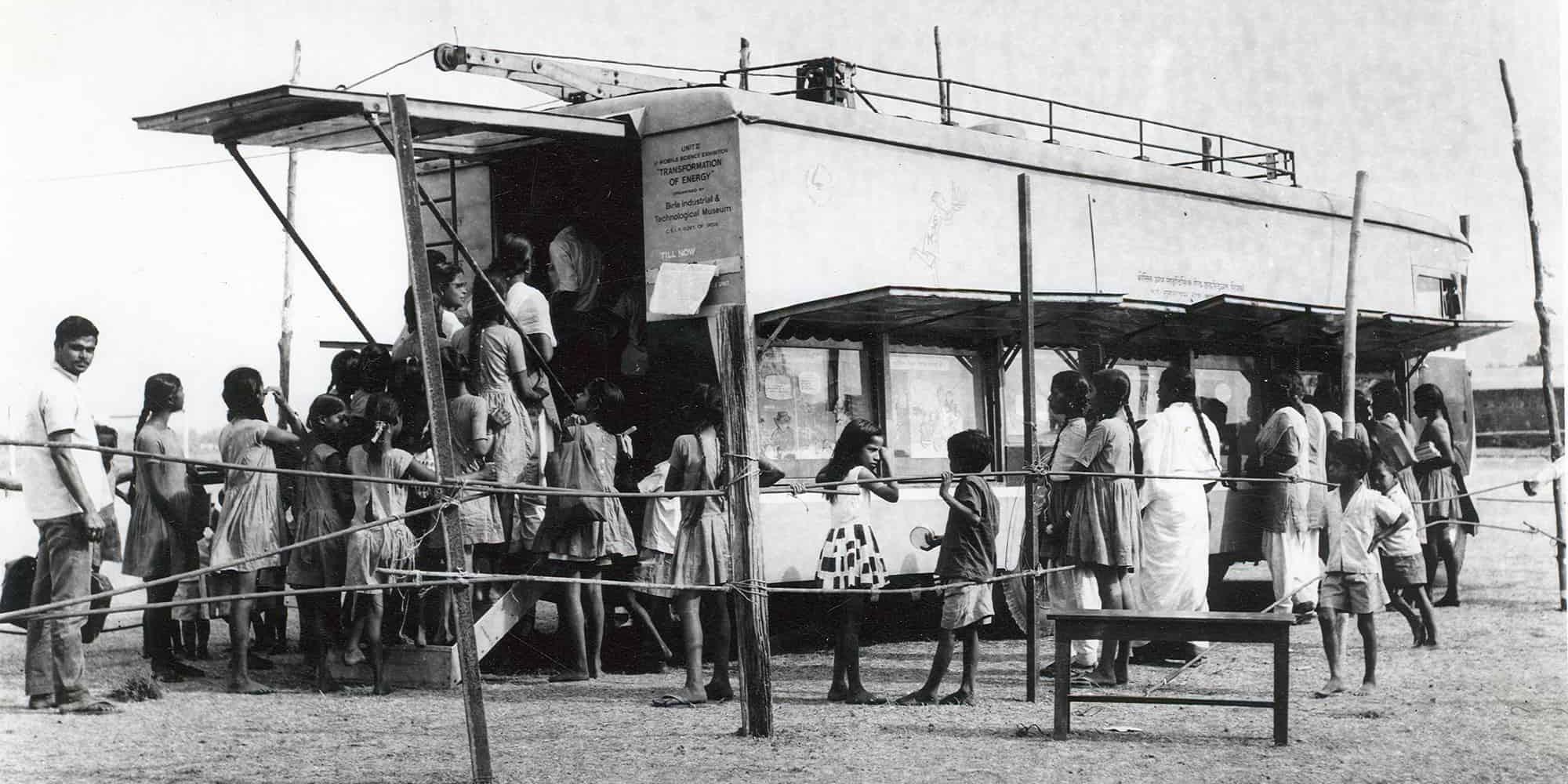

According to Hindu scriptures, a Brahmin is called dwija meaning somebody who is born twice. Mobile Science Museum (MSM) was born twice - first time on 17 November, 1965 in Ramakrishna Mission School in Narendrapur by Shri Prafulla Chandra Sen, Chief Minister of West Bengal, and the second time on 26 December, 1966 in Barsul Vijnan Mandir near Shaktigarh in the district of Burdwan.

Inaugural ceremony of Mobile Science Museum in Narendrapur Ramakrishna Mission School on 17 November, 1965 by Shri Prafulla Chandra Sen, then Chief Minister of West Bengal

Inaugural ceremony of Mobile Science Museum in Narendrapur Ramakrishna Mission School on 17 November, 1965 by Shri Prafulla Chandra Sen, then Chief Minister of West Bengal

The reason for this double inauguration was our self-imposed deadline of 14 November, the National Children's Day. While exhibit development work was in full swing based on its ultimate installation on a Museobus, the delay in securing necessary extra-budgetary fund stalled the placement of order for a suitable chassis and specially designed bus body. Pending settlement of this issue, we decided to go ahead for a travelling science exhibition on 'Our Familiar Electricity', mounted on tubular stands which could easily be dismantled or set up in a school or any other public place in district towns, and carried by an ordinary truck from place to place. The first MSM, developed on the subject 'Our Familiar Electricity', was mounted on tubular display stands and was inaugurated in Narendrapur in 1965.

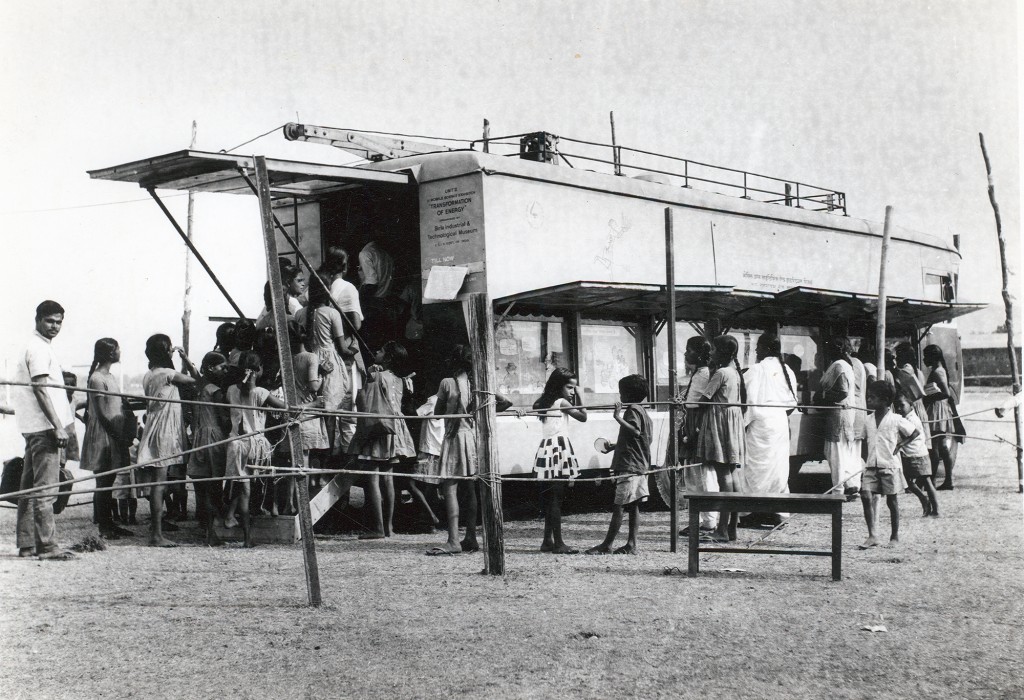

Inauguration of the first Museuobus at Vijnan Mandir in Barsul, Burdwan on 26th December 1966

Inauguration of the first Museuobus at Vijnan Mandir in Barsul, Burdwan on 26th December 1966

We were fully aware of the limitation of this kind of travelling exhibit, mounted on tubular stands and carried by a truck, as such an exhibition could be held only where a fairly large hall is available for setting up the exhibit, and this facility is available only in district towns. In order to increase the penetrative power of the exhibit, it was felt necessary to place it on a bus which itself would serve as the exhibition hall and hold exhibitions in the deep interior. A specially designed museobus was built on a standard truck chassis with twenty eight working exhibits on 'Transformation of Energy' and was inaugurated in Barsul Vijnan Mandir in 1966.

Experiments with Museobus

Shasanka Sekhar Ghosh, assisted by D Basu, burnt a lot of midnight oil to design a Museobus that suits all our requirements. For optimum utilisation of space, exhibits need to be installed at two levels – half of the exhibits, installed on the floor of the bus, facing outside, were at the eye level of visitors standing on the ground, while the other half installed on the upper level to be viewed by visitors standing inside the bus. The first Museobus, accommodating 28 exhibits, seven in a row, required a special permission from Motor Vehicles Authority for 32 feet length and 8 feet breadth. At a later stage it was found too difficult to manoeuvre a bus of this length in narrow roads.

First Trailer and Tractor Model of MSE Bus

First Trailer and Tractor Model of MSE Bus

Simultaneously with the Museobus, another major extension project was started by Samar Kumar Bagchi. This was the School Demonstration Lecture (SDL) program for complementing science education in schools with the help of low cost teaching aids. Initially the lectures were delivered in the museum auditorium, but with the Museobus on road, SDL kits were sent along with the bus for delivering lectures in the host schools. Ideas emerged at this stage for developing trailer buses so that the exhibit on the trailer may remain on show in the host school and the driving unit can be used for holding SDL in neighbouring schools. Two such trailer buses were developed and put on road. Like the first Museobus, the two trailer buses also were difficult to manoeuvre, particularly for entering through a narrow school gate. These trailer buses were later discontinued.

The next experiment was done by Achyut Keshav Date in Nehru Science Centre in Bombay. With the overall width of 8 feet, the Museobus does not have adequate space for visitor’s movement inside the bus. Date designed a bus with expandable body, where the two side wings could be pulled out to make more space at the centre during exhibition period, and could be collapsed to the overall width of 8 feet when running on road. This bus was run by Nehru Science Centre for years of its normal life span.

NCSM now runs a fleet of 25 Museobuses. Experience shows that the best manoeuvrable Museobus would be an integrated bus body like the first Museobus developed in 1966 but of smaller length to accommodate a total of 20 or at most 24 exhibits in four rows.

Exhibit Development

The exhibits were developed on subjects relevant to the everyday life of a common man in rural areas. The subject of the first exhibition was ‘Our Familiar Electricity’, containing 28 working exhibits dealing with the safety requirements in household wirings, proper use of common electrical appliances, and conservation of electrical energy. The second exhibit of the same size, installed in the first Museobus, was on 'Transformation of Energy' dealing with different forms of conventional as well as renewable sources of energy, transformation, conservation and recycling of energy. The third set of 24 exhibits, developed in BITM, was on 'Light & Sight' dealing with physics of light and physiology of sight. The BITM exhibits were designed and developed by Saroj Ghose assisted by a team consisting of Rabish Chandra Chunder, Ashok Kumar Dutta and Santibrata Som.

Dr. Saroj Ghose and R.C. Chunder working on exhibit development of MSE on 'Light and Sight'

Dr. Saroj Ghose and R.C. Chunder working on exhibit development of MSE on 'Light and Sight'

The activity soon gathered momentum in the sister museum, Visvesvaraya Industrial & Technological Museum in Bangalore. Rathindra Mohan Chakraborti, with graphic assistance from Amit Kumar Sarkar, developed new exhibits on 'Man Must Measure', 'Water, the Fountain of Life', and continued the activity further in Nehru Science Centre after developing new sets of mobile exhibits on 'Perception'.

Design of mobile exhibits takes into consideration a range of practical problems and apparently contradictory requirements. The exhibits must work, but with a minimum of moving parts because of humps and bumps on the road. They must be intriguing to create and sustain public interest, but must be simple and easy to maintain on the road. For interchangeability of exhibits between units operated by different museums, all exhibits must be encased in uniformly sized cabinets (3'1" x 2'1" x 1'), and yet they must look different to break monotony. Explanatory texts must be in local language for better understanding, but must be written on small detachable plug-in type boards so that the language can easily be changed while travelling in a multi-lingual country where spoken and written language changes every three hundred kilometres.

Programming and Activities

Programming for MSM was an elaborate exercise. Exhibitions were generally held in rural schools, the only infrastructure available in the deep interior areas, for three days in a place and the unit would hop to another site about 20-30 km away. In addition to the students and teachers of the host school, all neighbouring schools were invited to visit the exhibition in three days time. In this manner it was possible to cover a district in two to three months. The Museobus had to be on road for nine months a year and no exhibition was to be held within 50 km radius from the parent museum for the reason that the people near the parent museum at Calcutta or Bangalore would visit the parent museum in any case, and the purpose of MSM was to serve the people who do not come from the interior areas. Programming was done for a district about three months in advance in consultation with the District Inspector of Schools or District Education Officer with due consideration of roadworthiness of the place as well as easy connectivity for the neighbouring schools for their visit.

Each unit had its own portable petrol or diesel generator to run the exhibition in non-electrified areas, and a 16 mm film projector (prior to the video age) with a good stock of science education films for the evening programmes. At a later stage, some of the museobuses carried a portable inflatable-dome planetarium which could be set up in a school room for planetarium demonstration and astronomy education. Some museobuses carried a science demonstration lecture unit for improvisation of curricular teaching in schools.

Failures and Rewards

With the visible success of mobile exhibitions, several museums in the country approached BITM for the design of Museobus with a view to introduce similar activities in their institutions. National Museum and National Museum of Natural History at Delhi, Indian Museum and Jute Technological Research Institute at Calcutta, and Salarjung Museum in Hyderabad, all commissioned their Museobus with great fun fare. They first made week long trips, then cut down the activities to day trips, then the buses were seen stationed in respective museums and finally auctioned as scraps.

All these institutions mounted replicas, sometimes of poor quality, of their holdings which virtually had no operation and maintenance problem on road, still it was not possible for them to continue this activity of mobile exhibition. Moving the mobile units every three days for nine months a year, according to a schedule drawn up well in advance and keeping all exhibits working on the road require very careful planning and logistic support. The accompanying team of guide lecturer, driver and technician/cleaner needs to be changed at reasonable intervals, and the medical fitness of ageing staff for frequent travelling duties is to be kept under consideration. Such a program needs a special kind of long term commitment. It is easy to commission a mobile unit through one time effort, but far more difficult to keep it running.

The work was hard but looking at the response of the people it appeared rewarding. Mobile Science Museum was something like a festival of science in interior areas, otherwise starved of that kind of entertainment. What excited the young minds most was the students’ participation in the demonstration of exhibits. The MSM was accompanied by an education assistant or guide lecturer (who was the team leader), a technician and a driver. This team was inadequate for demonstration before a large audience. For that reason and also for involving the local students in the programme, a group of about twenty senior class students was trained in demonstration by the guide lecturer immediately on arrival, and thereafter the demonstration was given by those students throughout the period of exhibition. This system instilled a sense of responsibility and personal involvement among the local students who were elevated from the status of passive audience to active organisers. Their participation as demonstrators was self-gratifying for the parents and teachers and in the process increased the social acceptability of such activities.

For Whom the Bell Tolls

Questions were raised at some point of time on why the Museobuses hold exhibitions only in schools where non-school going communities might feel shy to visit. For whom the bell tolls when a Museobus reaches a small locality - the school children or the entire community? The answer is simple. The Museobus is for one and all, but the venue is usually a school because that is the only infrastructure available in a small locality having a secured space for parking the bus, ensuring a captive audience of receptive school children and offering modest hospitality to the accompanying staff members.

In his inaugural speech, the Chief Minister stressed on the need for developing travelling exhibits on subjects like agriculture for the benefit of farmers. Although we politely accepted his suggestion, it took almost a decade for the BITM or other science centres to develop travelling exhibits on socially relevant subjects like agriculture or environment or food & nutrition. What could be the reason for this inordinate delay? Was it due to typical physics bias of science centres, or somewhat city-centric approach of museum curators or their tilt towards school children who are more fascinated by magical performance of physical science? It is hard to pinpoint one or several reasons but a statement made by the legendary Frank Openheimer, the father of hands-on interactive exhibits, comes in mind. Asked what were the basic norms of his identification of subjects for development of exhibits, he said 'I pick up only such subjects on which interactive exhibits could be developed'. Probably in the beginning years we were too much obsessed with our commitment to interactivity. Socially relevant exhibits could be animated but not necessarily be made interactive!

MSM or MSE?

Mobile Science Museum (MSM), introduced in BITM in 1965, was a path maker but in less than a decade it lost its identity and the name was changed to Mobile Science Exhibition (MSE). The reason, as cited by some of our senior colleagues, was that the pre-requisite of a museum is original artefacts which were non-existent in MSM units. 'Exhibition' was more an appropriate term for the concept and contents of a mobile unit. The argument requires a more careful examination.

The word ‘museum’ is derived from Greek Mouseion, meaning the seat of the Muses. In Latin, museum is the place for learning occupation. Popular English dictionaries identify the museum with ‘a building in which objects of interest or significance are stored and exhibited’ or ‘a building where objects of historical, scientific or artistic interest are kept’. For about two centuries, museums were confined within the four walls of a building having collection of artefacts.

The growing public demand in the post-World War II period changed the character of museums in two major ways. First, the museums started developing educational activities with specially designed, cultivated and fabricated exhibits and teaching aids in addition to collected artefacts. With these didactic exhibits, the museums organise extensive outreach activities to reach the communities outside its four walls. Secondly, in addition to institutions traditionally designated as museums, various kinds of site museums, eco museums, nature reserves, now qualify as museums as per the definition laid down in the statutes of the International Council of Museums (ICOM). In the same ICOM statutes, planetaria and hands-on science centres, not having any original artefacts for collection, conservation and presentation, are also classified as museums. Artefacts and four walls are no longer pre-requisites of a museum. Today museum is a generic term for which the Museobus could very well be renamed as Mobile Science Museum.

Dr. Saroj Ghose is former Director General of National Council of Science Museums and Past President of ICOM (The International Council of Museums). He is presently Museum Advisor to the President of India and Science Centre of Yemen. He is behind Mobile Science Exhibition Program and development of Science City, Kolkata.